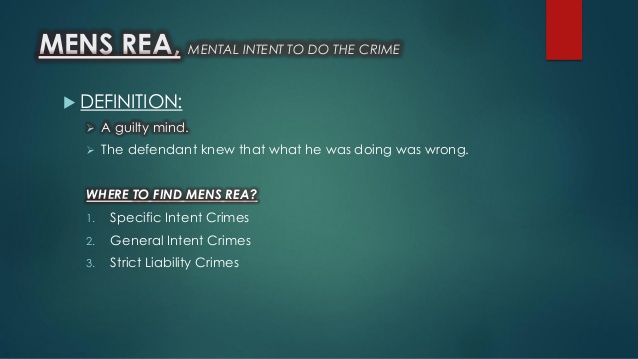

Most crimes require what the lawyers call “mens rea”, which is simply a Latin phrase which means “guilty mind”. In other words, what the defendant was thinking and the intention to commit the crime is irrelevant. The element of mens rea allows the criminal justice system to differentiate between someone who had no intention of committing a crime and someone who intentionally set out to commit the crime.

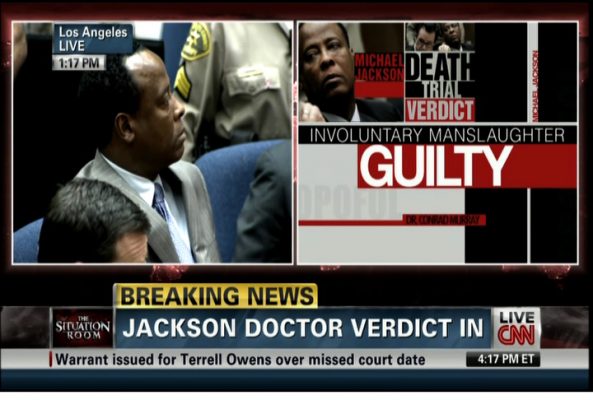

[If you are charged for a crime, it is important to contact a lawyer immediately to protect and analyze their rights.]To give an example, imagine two drivers who end up hitting and killing a pedestrian. The driver 1 never saw the person until it was too late, did everything possible to stop, but could do nothing to stop the accident and ended up killing the pedestrian. The driver 1 is still liable, but likely only need to answer before a civil court for monetary damages.

The 2-conductor, for his part, had gone out in search of the pedestrian and, seeing him, turned towards him, floor the accelerator pedal, was launched against him and killed him instantly. The conductor 2 is likely to have criminal responsibility because he had the intention to kill the pedestrian, or at least had the intent to cause serious bodily injury. Despite the fact that the pedestrian dies in both situations (the result is the same), the intentions of the two conductors were not the same and, accordingly, their punishment will be substantially different.

Reckless in Front of Criminal

Recklessness is known as “negligence” in legal terminology, and, in general, generates only civil liability and not criminal. However, at some point the recklessness usually turns into something more culpable, and some criminal statutes have stated standards of negligence, such as criminal negligence or reckless. For example, it may be simple negligence to leave objects about your sidewalk that cause a neighbor to fall and get hurt. However, it can be more than simple negligence if you leave out a saw, some knives and flammable materials in your sidewalk, causing severe injuries to his neighbor.

Intentional Versus Unintentional

The conduct detrimental to deliberate is often criminal, but the disruptive behavior involuntary is presented in two basic forms. The first is the “mistake of fact” and the second is the “error of law”.

The mistake of fact means that, despite the fact that their behavior conforms to the definition of a crime in an objective sense (e.g., sold illegal drugs), I was not aware that what he was selling was in fact an illegal drug. For example, if you gave someone a bag full of white powder in exchange for some money, and honestly thought it was baking soda, then you are mistaken as to a fact which is fundamental to the crime. As a result, it is likely that absent the element of mens rea required, or the mental intent necessary under drug laws, as they never had the intention of selling an illegal drug, but that he intended to sell baking soda (keep in mind that almost no one will believe that you honestly thought that baking soda could be sold for that amount of money).

However, the mistake of law almost never save you from criminal liability. Almost everyone is familiar with the phrase that “ignorance of the law is no excuse”, and that is exactly the way that he sees the law. Perhaps in the above example, I knew that what I was selling was cocaine, but I honestly thought it was legal to do so. It doesn’t matter. It may seem a little unfair that the person who was so foolish as to believe that the white powder was sodium bicarbonate is free and that the well-intentioned person who in truth thought that it was legal to sell cocaine go to prison. The justification of having no margin for ignorance of the law is based on that to allow ignorance of the law as a defense would be to discourage people to know the law and undermine the effectiveness of the legal system.

Strict liability and Mens Rea is Not Required

Finally, there are some criminal laws, called laws of strict liability, which does not require any element of mens rea at all. These laws are justified in affirming that no matter what you intended, the act itself deserves a criminal punishment. Many laws of strict liability involving minors, such as laws prohibiting “statutory rape” and the sale of alcohol to minors. It does not matter that you believed honestly that the child was 18 years of age in the case of rape or 21 years or older in the case of the sale of alcohol. These laws often seem harsh, but the theory that lies behind them is the protection of the minor over the possible innocence of the accused.

To commit a Crime “With Knowledge”

Many criminal laws require a person to participate “knowingly” in illicit activities. What part of the crime must be done with knowledge depends on the crime. For example, an act of drug trafficking may require that the person amount “with knowledge” an illicit drug in the united States. If the defendant had given a gift to deliver to someone in the united States, and the defendant honestly did not know that the gift contained an illegal drug, then there was the necessary element of mens rea and did not commit any crime.

Committing a Crime “Maliciously” or “Voluntary”

Some criminal laws use the terms “malicious” and “voluntary” to describe the conduct necessary. Generally, this does not add anything that is not already covered in the intent and knowledge. However, in some of the laws on homicide is an “aggravated” of intent/knowledge, and will result in a charge for murder in the highest degree. The difference is that it is one thing to get angry with someone and kill him in a moment of passion, but it is quite another to devise a plan to stalk and kill a victim.

Despite the standard almost adamant that ignorance of the law is no excuse, sometimes “willfully” has been interpreted as knowing that it is illegal and do it anyway (that requires to know that the law classifies as illegal).

Commit a Crime with the “Specific Intent”

Crimes with a specific intent are crimes in which an act has to be accompanied by a particular intention to do something, and is often written as “[performed a physical act] with the intention of doing so”. An easy example to understand is theft.

Most of the laws on theft requires that you not only take an object (the physical act), but take it with the intent to “deprive permanently” the rightful owner of that object. For example, imagine that you took of your friends a pair of sunglasses for the day, but did so with the intention of returning it that same afternoon. She had No right to take those glasses, they belong to your friend, but what he did was not a theft because she never had the intention of staying permanently with the sunglasses.

The Importance of the Reason

The reason for this is an indirect way to prove that something was done intentionally or with knowledge. For example, a defendant in a case of assault can be said that hit the victim by accident and that, therefore, did not have the necessary intent for an assault (that is to say, the intent to cause bodily harm). However, if the prosecution can show that the defendant and the victim had been discussed shortly before the alleged assault, that reason can serve as circumstantial evidence that the defendant actually had the intention of hitting the victim. As an alternative, defendants may use the lack of evidence of a motive on the part of the prosecutor’s office as a “reasonable doubt” to avoid criminal liability.

How To Get Legal Help

The process of the criminal law can be very difficult with a lot of stress. If charged for a crime, it is important to contact a lawyer immediately to analyze the facts of the case and protect your rights.